Extra Intestinal Manifestations – The Liver

Disclaimer: This information is based on my own research into this particular extra intestinal manifestation of IBD as well as some personal experience and should not be used as medical advice or a diagnostic tool. The suggested investigations and prevalence are part of the IBD protocols set out by NICE; but do vary between CCGs and then thus individual NHS Trusts and specific hospitals. If you seek advice regarding the things you experience within your own disease, please contact your IBD team for medical advice.

This new series looks at the effects IBD can have beyond the gut. As a whole, extra intestinal manifestations of IBD occur when the disease is not controlled well enough with conventional medications. However, the side effects of particular medications can produce new symptoms which would mirror or mimic these extra intestinal manifestations (EIMs). For all of the information provided in this series, I have gathered resources and broken them down, putting them into patient speak. Each post comes with a disclaimer too (see the end of the post) so if you have concerns, you should see your specialist in all instances.

The Liver

Complications with the liver occur when there is a problem with how well it can perform its function. The liver acts as a filtration system, taking in what we ingest and helping to break it down into waste as well as useable materials. The liver produces cholesterol, acids, and bile salts that get stored in the gallbladder until required. In some of those with IBD, the liver can become inflamed or damaged. Most liver damage is reversible, but serious liver disease can affect about 5% of people with IBD.

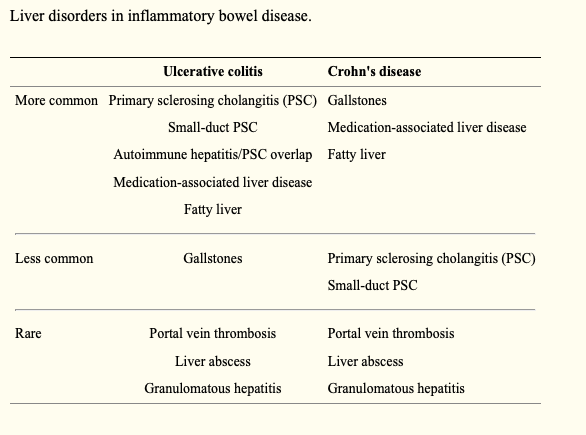

This post will look at fatty liver disease (FLD), Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and medication-associated liver disease (MLD).

Who is affected?

Up to 50% of patients with IBD are affected by hepatobiliary manifestations during the course of their disease. PSC, small-duct PSC, fatty liver disease, granulomatous hepatitis, autoimmune liver and pancreas disease, cholestasis, gallstone formation, and liver injury are hepatobiliary manifestations of IBD.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of liver inflammation include low energy or fatigue. Many times, patients are asymptomatic. More advanced liver damage leads to a feeling of fullness or pain in the upper right abdomen, itching, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes), easy bruising, fatigue, and fluid retention.

Diagnosis

Blood tests can usually confirm the presence of liver disease, although ultrasound, CT scan and MRI scan, as well as other tests, including endoscopic examination of the bile ducts or liver biopsy, may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

It is recommended that a multidisciplinary approach is appropriate to manage liver complications. Any patient with IBD and elevated liver function tests should warrant co-managment with a Hepatologist, as orthotropic liver transplantation is the only curative treatment. A surgical consultation should also be obtained if there is any possibility of cholangiocarcinoma or colorectal cancer.

Fatty Liver Disease

or Hepatic Steatosis is the most common liver complication of IBD and is often reversible, affecting people with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease equally. This is a condition whereby extra fat gets deposited in the liver, squeezing out normal liver cells. This can happen in other conditions as well, like diabetes, pregnancy, and obesity; as well as being due to steroid use. No specific treatment is necessary as it does not cause any symptoms, but weight loss along with control of blood cholesterol levels will usually rid the liver of the extra fat and should be encouraged in any patient that has fat deposits.

Hepatitis

is a non-specific term for inflammation of the liver. It can be caused by medications like Methotrexate (MXT), Azathioprine, 6-Mercaptopurine (6MP) or rarely anti-TNF agents. Your doctor should do periodic blood tests to monitor for this condition. Hepatitis can also be caused from inflammation of the liver itself related to a person’s IBD, called Autoimmune Hepatitis. It is treated with the same kinds of medicine that UC and Crohn’s disease are treated with, to decrease the inflammation. Autoimmune hepatitis, however, can lead to liver scarring (cirrhosis) and permanent liver damage if not treated. Hepatitis can also be from viruses like Hepatitis A, B, or C and should be treated the same as in patients without IBD.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC)

is form of inflammation specific to the bile duct system of the liver. Bile ducts transport bile from the liver to the upper small intestine. PSC is seen in about 5-10% of patients with ulcerative colitis but less in Crohn’s disease. Some patients with PSC do not have IBD. Causes inflammation, fibrosis leading to strictures in the bile ducts and eventually the liver is damaged. When this occurs, the bile cannot flow normally. Bile buildup leads the patient becoming symptomatic including, Common symptoms are fever, chills, abnormal LFT, RUQ abdominal pain, dark urine, itching (pruritus) and jaundice. If there is enough damage, fatigue can occur. Unfortunately there is no treatment for this condition. To control the bile build-up, stents are usually placed within the bile ducts to keep the bile flowing. Complications of PSC include infection of the bile (cholangitis) and cancer of the bile duct system (cholangiocarcinoma; about a 5-15% rate). If the liver is damaged too much, cirrhosis can occur and liver transplantation can be considered. Another complication in patients with PSC is an increased risk for colon cancer. So it is important for patients with PSC to speak to their doctor about undergoing annual surveillance colonoscopies.

It is more likely in those UC patients with extensive colonic involvement, those between 30–59 years of age, with a 2:1 male prevalence for the disorder. The clinical course of PSC bears no relationship to underlying bowel disease, and PSC can develop either years before or after the development of bowel symptoms.

Laboratory abnormalities will show an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level; in contrast, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are typically normal. Albumin levels and prothrombin time are typically normal until the development of advanced disease and cirrhosis. Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the test of choice for diagnosis.

Medication-Associated Liver Disease

Sulfasalazine

- Mesalamine (Asacol, Pentasa)

- Sulfasalazine (Sulfazine)

This class of medication is made up of sulfapyridine and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA). Sulfasalazine plays an important role in both the induction and maintenance of remission in IBD; specifically those with Colitis, or those with Crohn’s Colitis. Hypersensitivity to sulfasalazine can induce chemical-driven liver damage which manifests as elevation of liver aminotransferases (ALT & AST), jaundice, hepatomegaly (abnormal enlargement of the liver), fever, and lymphadenopathy (disease of the lymph nodes). Studies have shown that the 5-ASA component of the medication can induce both an acute and a chronic hepatitis which can occur from anywhere between 6 days to 1 year after the initiation of treatment, but the frequency of hepatitis is no different between the 5-ASA alone and sulfasalazine.

Monthly blood testing of all liver functions should be done to ensure hepatotoxicity is monitored, before being moved to 3 monthly testing.

Thiopurines

- Azathioprine (Imuran)

- Mercaptopurine (Purinethol)

- Thioguanine (6-TG, Tabloid).

Thiopurines (Azathioprine and 6-Mercaptopurine) are immunomodulators used in the treatment of IBD. Hepatotoxicity can occur with the use of Azathioprine (AZA) or 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) due to the effect of another metabolite, 6 methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP). By measuring the levels of thioguanine nucleo- tides (TGNs) – one the key components of Thioprine metabolism – the correct dosage can be established and hopefully avoid liver complications. Checking TGNs in all patients 4 weeks after starting thiopurines or following a change in the dose has been fundamentally in lowering the raise of acute toxicity within the liver. The onset of response from thiopurines is around 16 weeks so if being prescribed as monotherapy, bridging with corticosteroids or an alternative therapy should be considered.

In instances where TGNs are subtherapeutic, increasing the dose by between 25 mg and 50 mg may be enough for TGNs to reach the therapeutic range. It can also be recommended either switching to Allopurinol or dose splitting. With this, regular repeat LFT & FBC blood work should be completed on a monthly basis.

Above is the management of deranged FBC in thiopurine patients. These established a pathway for decision making for limiting the patient’s exposure to long term complications. However, discontinuation of these medications most often leads to reversal of the acute toxicity; but in some instances the development of severe cholestasis may not improve despite withdrawal of the medications.

Methotrexate

Toxicity from Methotrexate is unusually seen. This may be related to perceived side effects of MTX, particularly given the toxicities seen at higher doses in cancer chemotherapy. Also, European guidelines only recommend MTX as a second or third line therapy in CD after failure of thiopurine and/or anti-TNF therapy. However, with the lower doses, weekly regimens and the concomitant use of folic acid; Methotrexate is a useful treatment option for IBD patients.

Methotrexate may promote a rise of liver enzymes, which is observed in 3–33% of IBD patients treated with MTX and necessitates discontinuing therapy in around 6–8%. Recommendations for stopping therapy are based on degree of absolute change in liver enzymes and the duration of abnormalities on serial measurements. Underlying liver diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes or excess alcohol consumption are important co factors for MTX induced liver toxicity. There are no clear guidelines for the monitoring of liver functions in IBD patients on methotrexate, and liver toxicity may become apparent at anytime with the use of this medication.

A typical approach may be to have blood tests every 1-2 weeks until your condition is stable on the treatment, and then every 2-3 months thereafter

Biologic Agents

Biologic agents such as Infliximab and Adalimumab have been associated with hepatotoxicity. These medications interfere with the activity of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF α) which plays a role in hepatocyte regeneration, hence the possible link with the development of hepatotoxicity which is still an uncommon side effect with this group of medications.

Patients with chronic hepatitis secondary to hepatitis B or C may have reactivation of the disease and viral replication as a result of immunosuppression from biologic agents. Due to the grave implications of reactivation of hepatitis B or C virus in immunosuppressed patients, guidelines have been proposed for the routine screening of patients for these viruses before starting biologic agents.

The optimal management of liver injury induced by anti-TNF therapy is still not consensual. The prognosis is generally good, with most patients presenting with mild elevation in liver enzymes resolving spontaneously with continuation of anti-TNF therapy. A consensus statement proposes more restrictive criteria; with avoidance or discontinuation of treatment in patients with transaminases superior to 3 times the upper limit of normal. Ideally, before initiation of treatment, a baseline panel of liver enzymes should be obtained, together with a determination of HepB and HepC virus status. After initiation of treatment, liver enzymes should be monitored periodically, especially during the first three months. When faced with an elevation of liver enzymes, other causes should be excluded. In case of minor elevations of ALT (< 3 times the upper limit of normal), anti-TNF may be continued with close monitoring until resolution. If the enzymes are persistently elevated, superior to 3 times the upper limit of normal or in case of alarm signals such as jaundice; a multidisciplinary approach with refer to an Hepatologist and consideration for corticosteroid treatment is advised. A liver biopsy may be useful in this context. Even if a drug induce liver injury is documented, anti-TNF withdrawal remains controversial.

My experience

I have had issues with my liver for almost five years now. It was accidently found out from a blood test I had taken one evening in A&E after a long period of vomiting. Since then, I’ve really struggled to get my LFTs within the parameters of what is considered ‘normal’, even with IBD. During my surgeries, it was closely monitored too. I have now seen two liver specialists; who have ‘shotgunned’ me for every test to find the diagnosis for my elevated LFTs. I’m currently on the final procedure which should give me a diagnosis, but we can never be 100% sure. My own experience is now leaning toward drug induced injury as I have been on alot of the trigger IBD medication, and so far, Vedolizumab – my current treatment plan – is not providing data on liver injury.

For me,I would take my current position – liver injury with monitoring and my Vedolizumab – than be removed off my treatment and see if my liver improves. My IBD tends to flare wildly when not on medication. But it could come to that. It is always a risk, taking a new medication for IBD and I’ve always looked at the benefits and risks, when deciding. And for me, the benefits at the time of starting treatments, have always outweighed the risks.

Next time… we explore when and how IBD can affect the eyes.

Do you have any questions or queries? Or just want to share your own experiences? You can leave me a reply here or leave comments via my social media accounts – on Twitter, find my blog page on Facebook and over on Instagram

Further Reading:

Crohns Colitis Foundation, Dr Kim of UCSD School of Medicine – Extraintestinal Manifestations of IBD

NCBI – Gastroenterology & Heptology – Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (April 2011)

NCBI – Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (August 2015)

NCBI – Gastroenterology Research & Practice – Liver Disorders in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (2012)

Crohns Colitis Foundation – Liver Complications (pdf, fact sheet)

BMJ – Frontline Gastroenterology – A Practical Guide to Thiopurine Prescribing and Monitoring in IBD (August 2016)

NCBI – Use of Methotrexate in the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) (January 2016)

NCBI – World Journal of Heptology – Hepatic Complications induced by Immunosupprssants and Biologicals in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (May 2017)

Disclaimer: This information is based on my own research into this particular extra intestinal manifestation of IBD as well as some personal experience and should not be used as medical advice. The suggested investigations and prevalence are part of the IBD protocols set out by NICE; but do vary between individual NHS Trusts and specific hospitals. If you seek advice regarding the things you experience within your own disease, please contact your IBD team for medical advice.