The Digestive System: Part I – Anatomy

What exactly is the ‘Digestive System’?

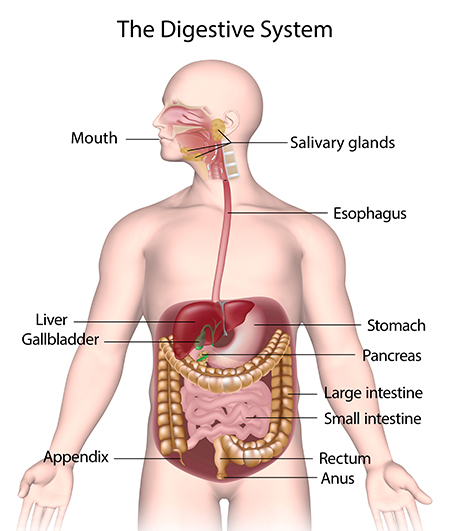

When we say ‘digestive system‘ we are referring to the system within our body which helps us process food. Included this system is the gastrointestinal (GI) tract along with the liver, pancreas and gallbladder. The GI – or Digestive – Tract consists of a series of hollow organs which connect to a long, twisting hollow tube from the mouth to anus. These organs are the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system.

The small intestines consist of three parts – the duodenum, the jejunum and finally the ileum. The large intestine, in turn, consists of the appendix, cecum, colon, and rectum. The diagram below shows the locations of each aspect in proximity to each other:

How does it work?

Each part of your digestive system helps a) to move food and liquid through your GI tract, b) break food and liquid into smaller parts, or c) both. Once foods are broken into small enough parts, your body can then absorb and move the nutrients to where they are needed. Your large intestine absorbs the remaining water, and the waste products of the entire process of digestion become stool. The digestive process is controlled by nerves and hormones within your body. As well as this, bacteria naturally occurring in your GI tract – also called gut flora or microbiome – help greatly with digestion. Some parts of your nervous and circulatory systems also help. Working together; nerves, hormones, bacteria, blood, and the organs of your digestive system digest the foods and liquids you eat or drink each day. This is all done without a thought, a subconscious and natural part of being a human being.

Why is digestion important?

Digestion is important because your body needs nutrients from food and drink to work properly and to stay healthy. Proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and water are all nutrients. Your digestive system breaks nutrients into parts small enough for your body to absorb and uses them for energy, growth, and cell repair.

- Proteins break into amino acids

- Fats break into fatty acids and glycerol

- Carbohydrates break into simple sugars

How does food move through my GI tract?

Food moves through your digestive system by a process called peristalsis. Within your small intestine and colon, there is a muscle within the wall of the tubing which enables movement. It is this – an involuntary constriction and relaxation of the muscle, creating wave-like movement – which pushes food and liquid through your system and mixes the contents within each organ. As well as the use of peristalsis to move food through your GI tract, your digestive organs also break food into smaller parts using digestive juices; such as stomach acid, bile, and enzymes.

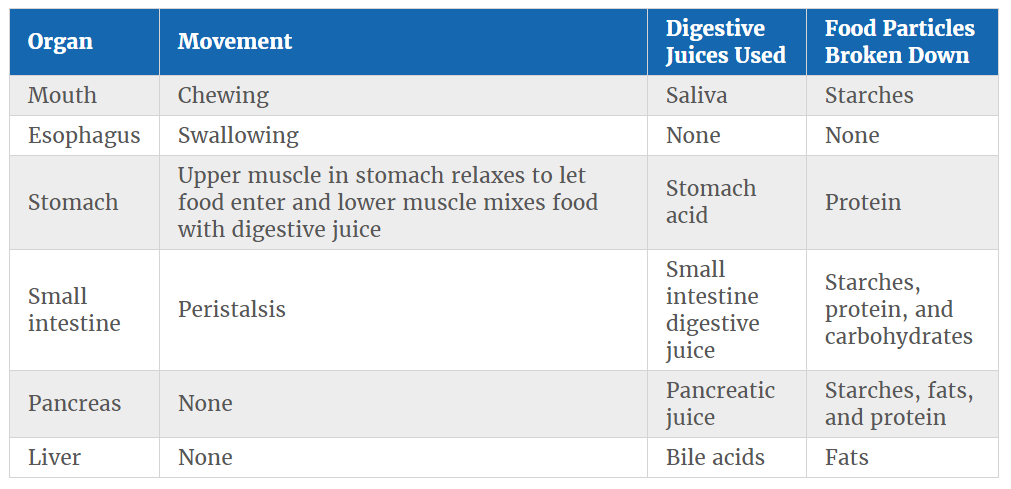

The below table shows what each aspect of your digestive system does:

Functions

Mouth – is the beginning of the digestive tract. In fact, digestion starts here when taking the first bite of food. Chewing breaks the food into pieces that are more easily digested, while saliva mixes with food to begin the process of breaking it down into a form your body can absorb and use.

Esophagus – Located in your throat near your trachea (windpipe), the esophagus receives food from your mouth when you swallow. By means of a series of muscular contractions called peristalsis, the esophagus delivers food to your stomach.

Stomach – a hollow organ that holds food while it is being mixed with enzymes that continue the process of breaking down food into a usable form. Cells in the lining of the stomach secrete a strong acid and powerful enzymes that are responsible for the breakdown process. When the contents of the stomach are sufficiently processed, they are released into the small intestine.

Small intestine – Made up of three segments – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum – the small intestine is a 22-foot long muscular tube that breaks down food using enzymes released by the pancreas and bile from the liver. Peristalsis is also at work in this organ; moving food through and mixing it with digestive secretions from the pancreas and liver. The duodenum is largely responsible for the continuous breaking-down process, with the jejunum and ileum mainly responsible for absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream.

The contents of the small intestine start out semi-solid but end in a liquid form after passing through the organ. Water, bile, enzymes, and mucous contribute to the change in consistency. Once the nutrients have been absorbed and the leftover-food residue liquid has passed through the small intestine, it then moves on to the large intestine, or colon.

Pancreas – secretes digestive enzymes into the duodenum, the first segment of the small intestine. These enzymes break down protein, fats, and carbohydrates. The pancreas also makes insulin, secreting it directly into the bloodstream. Insulin is the chief hormone for metabolizing sugar.

Liver – The liver has multiple functions, but its main function within the digestive system is to process the nutrients absorbed from the small intestine. Bile from the liver secreted into the small intestine also plays an important role in digesting fat. In addition, the liver is the body’s chemical ‘factory’: it takes the raw materials absorbed by the intestine and makes all the various chemicals the body needs to function. The liver also detoxifies potentially harmful chemicals, as well as breaking down and secreting many drugs.

Gallbladder – The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile, and then releases it into the duodenum to help absorb and digest fats.

Colon (large intestine) – The colon is a 6-foot long muscular tube that connects the small intestine to the rectum. The large intestine is made up of the cecum, the ascending (right) colon, the transverse (across) colon, the descending (left) colon, and the sigmoid colon, which connects to the rectum. The large intestine is a highly specialized organ that is responsible for processing waste so that emptying the bowels is easy and convenient.

Stool – or the waste left over from the digestive process – is passed through the colon by means of peristalsis, first in a liquid state and ultimately in a solid form. As stool passes through the colon, water is removed. Stool is stored in the sigmoid colon until a ‘mass movement’ empties it into the rectum once or twice a day. It normally takes about 36 hours for stool to get through the colon. The stool itself is mostly food debris and bacteria. These bacteria perform several useful functions, such as synthesising various vitamins, processing waste products and food particles, as well as protecting against harmful bacteria. When the descending colon becomes full of stool – or feces as it then becomes known as – it empties its contents into the rectum to begin the process of elimination.

Rectum – The rectum (Latin for ‘straight’) is an 8-inch chamber that connects the colon to the anus. It is the rectum’s job to receive stool from the colon, to let the person know that there is stool to be evacuated, and to hold the stool until evacuation happens. When anything comes into the rectum, sensors send a message to the brain. The brain then decides if the rectal contents can be released or not. If they can, the sphincters relax and the rectum contracts, disposing its contents. If the contents cannot be disposed, the sphincter contracts and the rectum accommodates so that the sensation temporarily goes away.

Anus – The anus is the last part of the digestive tract. It is a 2-inch long canal consisting of the pelvic floor muscles and the two anal sphincters (internal and external). The lining of the upper anus is specialized to detect rectal contents. It lets you know whether the contents are liquid, gas, or solid. The anus is surrounded by sphincter muscles that are important in allowing control of stool. The pelvic floor muscle creates an angle between the rectum and the anus that stops stool from coming out when it is not supposed to. The internal sphincter is always tight, except when stool enters the rectum. It keeps us continent when we are asleep or otherwise unaware of the presence of stool. When we get an urge to go to the bathroom, we rely on our external sphincter to hold the stool until reaching a toilet, where it then relaxes to release the contents.

Next time… the focus is around how digestion and the system function when you have a digestive condition, such as IBD.

Do you have any questions or queries? Or just want to share your own experiences? You can leave me a reply here or leave comments via my social media accounts – on Twitter, find my blog page on Facebook and over on Instagram

Sources:

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases – Your Digestive System and How It Works

TED-Ed – How Your Digestive System Works (video)

Mayo Clinic – (slide show) See how your digestive system works

IBD Relief – What is the Digestive System and How Does it Work?

The IBD Clinic – How does Digestion Work

Cleveland Clinic – The Structure and Function of the Digestive System